Learning from Fab Lab Finland

Babken Chugaszyan is an alumni of Fab Academy, and the head of Fab Academy Armenia. While you may have heard of Fab Labs, maker-spaces equipped with digital manufacturing machines to “make almost anything”, you may be less familiar with Fab Academy, a rigorous program lead by the Director of MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms, Professor Neil Gershenfeld. Fab Academy is the world’s first example of distributed learning, a model that combines long distance learning (online coursework) with regional mentorships and partnerships to create nodes of communities around the globe. Today, at Fab Lab Armenia Education Foundation – Dilijan, Babken is a lead instructor for students enrolled in Fab Academy and oversees recruitment of prospective students. In January 2022, Babken went to Finland to participate in the Fab Academy Instructors’ Bootcamp, an annual training series that happens in different parts of the world. His experience in Finland was inspiring, and even “mind blowing” according to Babken. We sat down with Babken to learn more about what made Finland so special, and what takeaways he brought back with him to Armenia.

Was this your first trip to Finland?

Babken Chugaszyan: Yes, have you been? It’s amazing.

What was the most impressive thing you saw in Finland?

BC: There were so many, it’s hard to choose just one. But I think Aalto University really amazed me the most. It’s near Helsinki [in Espo, Finland]. For one thing, the architecture is very beautiful. Also, the departments – it’s a very rich place. In terms of facilities, resources…everything. And the people were so kind. I felt something special in this university.

They’re famous for Aalto Design Factory (ADF), a program and concept that first started in Aalto and that exists today in 38 countries around the world. It’s like the idea of Fab Lab in terms of equipment and the potential to make almost anything, but they focus on connecting universities to industries. This is the starting point for innovation.

They [ADF] have a Product Development Program (PDP), where they bring representatives from different companies together and identify their needs. Then they gather the students and figure out their interests. Next, they marry these needs together. Each industry [company] provides 15,000 EUR to the student so that he/she can solve their problem.

Industries don’t come for fun, they come for results. Finland has very developed industries and very developed universities. It’s impressive how they work together. I couldn’t say which one is more important in Finland. Put another way, do you need to have a good university in order to have good industry, or do you need good industry to have good universities? I’m not sure, but they have it right in Finland.

What was the weirdest or most unexpected thing you saw?

BC: I didn’t see it with my own eyes, but I learned about this habit they have taking their kids outside for naptime. It doesn’t matter how old they are, even little kids. And even if it’s -20 degrees outside. They believe that it’s very healthy and that kids sleep better when it’s cold.

What event/place/person inspired you the most?

BC: A few people really inspired me. Before going to Finland, I reached out to a group called “Armenians of Finland”, and said I was interested in visiting different educational institutions. Since I wanted to visit the Aalto Fab Lab, one girl reached out saying that she works there and could provide me a tour. Arpine was from Armenia but had completed her Ph.D. there. She was very helpful and gave me access to all kinds of spaces that I couldn’t have seen otherwise. She’s the one who introduced Aalto Design Factory to me.

She also told me about the Central Library of Finland, which is another impressive place. It has a Fab Lab within the library, and though it doesn’t run Fab Academy, it’s there specifically to serve the public. People can just book space, machines and pay for their materials and go.

Arpine also invited me to a gathering of Ph.D. students of Aalto, so I was able to meet a lot of different students from different departments. It was very enriching. I really would love to go to Aalto University. It’s not that famous in terms of international ranking, but there’s something special there. The professors, the environment….

I also had the chance to meet two Armenian engineers who had moved to Finland 30 years ago during the Soviet Union. They were scientists. It was very impressive what they were doing. They were on the edge of innovation, working at Nokia and Qualcomm, doing a lot of cool research on lensless cameras.

Finland used to be a very powerful center for telecom. Today a lot of manufacturing happens elsewhere but the expertise and professionals are still there. Most telecom companies have a base there because of the community of experts in Finland. These guys told me that Nokia really changed Finland. Before Nokia, Finland was much more “Gavarakan” (provincial), as we say in Armenian. Nokia transformed the culture, the economy, and created a real knowledge center. Samsung and other such companies all hired Nokia employees for their expertise.

Other people that inspired me were the guys running Design Factory. I had the chance to have a tour with Director Kalevi Ekman, who taught me about the history and philosophy of the place. Also, I had wonderful instructors from Fab Academy bootcamp from Amsterdam and Belgium. Then there was our host, Jani Ylioja, from Oulu Fab Lab who was amazing and highly organized – keeping us all on track. So many inspiring people.

How was the Fab Lab in Finland, and was it different from the one in Dilijan?

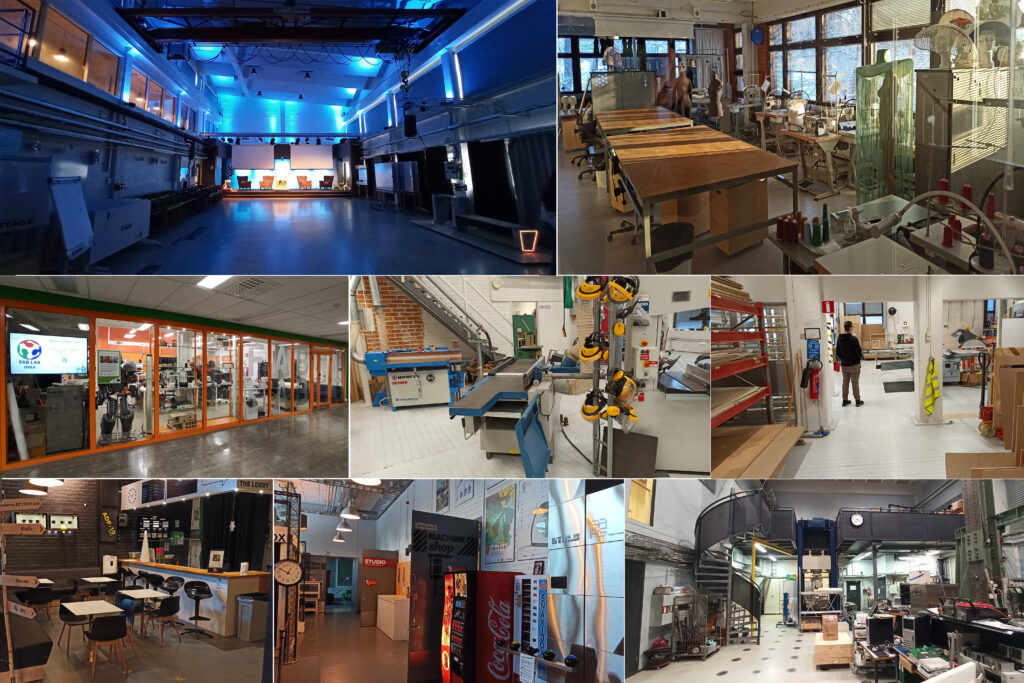

BC: I visited multiple Fab Labs: the Aalto Fab Lab, the Central Library Fab Lab, a maker’s space called Omnia Makerspace, the Design Factory, and the Oulu Fab Lab. There are more than that. There’s also an important one in Tampere, a city near Nokia, that’s connected to Tampere university where all these Nokia technologies emerged.

But to come back to your question. The Aalto University Fab Lab is one of the most impressive. First – how you get there. They built a metro station inside the university. So, when you come by metro, and step outside of the train, you’re immediately inside the university. And the first thing you see from there is the Art Department.

The Fab Lab is located inside the Art Department. So, my first impression was, “if this is your art department, I can’t imagine what your engineering department is like…”. And that’s how it was…their engineering department was crazy.

One of the distinctive things that stayed with me when comparing our Fab Lab with theirs was their machines. For example, they didn’t have a Shop Bot, a typical Fab Lab CNC machine (American produced), because it doesn’t comply with their safety standards. So instead, they have their own Finnish CNC machine. And the same is true for their 3D printers. For them it’s an ethical position. First, they give priority to Scandinavian products. Secondly, it’s a practical decision. They always make sure that there is support locally (a dealer, an expert or maintenance professional etc.). This is a huge cultural difference. We never try or think about purchasing an Armenian machine or Armenian alternative to what’s available on the market. And when we have problems (which we eventually do) we try to solve them by ourselves, and often we break the machine because we don’t know how to fix it. And sometimes it’s just not fixable, you just need to return a part to the dealer, and they give you a new piece. They don’t mess around where they shouldn’t.

How will you apply this experience to Dilijan Fab Lab?

BC: I’d have to say my learnings are classified in two categories. First, I have a new perspective on the organizational approach to machines and space. For example, the infrastructure they have around central vacuum systems and air cleaning. Finland has a lot of regulations which can initially seem like it makes everything complicated, but at the same time, these are things that make your life easier afterwards.

The second key learning was about how they organize work. By this I mean, for example if you go to Oulu Fab Lab, they have 9 employees just in the fab lab, and all 9 of them were Fab Academy graduates. The number of students they have at a time varies from 2 to 10 but imagine the student to instructor ratio. It’s a huge benefit to have so many mentors and experts available.

The other point is that both the Aalto and Oulu Fab Labs are located within universities, and those universities give scholarships to their Ph. D. students to complete Fab Academy. Rarely do they accept master’s level students. So, the work is very focused.

The other bit is that Fab Lab is just a piece of the university’s facilities. They have all kinds of other spaces: storage spaces for materials, massive scale machines for cutting any kind of material paneling. They have special sections or departments according to materials (like welding, woodshop, textiles etc.), and each workshop has it’s specialized in-house expert or studio manager.

Was there a program that you would like to see happen in Dilijan?

BC: Design Factory, which I’ve already mentioned was special. It began because in Finland there was a time when students complained that studies were too theoretical. The aim was to connect hands-on to theoretical. That’s how Design Factory was born. They wanted to connect industry and business to learners. The program has 35 courses, 6 departments, and you really feel that the students come first. The Design Factory motto is that it’s not the place, it’s the people. And though that could sound like a “buzz phrase”, they weren’t just words, you could really see that.

Are there any other learnings or take-aways from this trip?

BC: Well, like I said the thing that really impressed me was this cooperation between University and Industry. Also, the overall trust and kindness of people. There was so much information, I’m still digesting it. I’m not sure I could summarize key take-aways. But really one of the most important things that stayed with me was how they don’t waste time.

They are hyper efficient. They don’t have many human resources, they’re a small country of 5 million people. So, they really value people and their time. They don’t want to waste anyone’s time, and you can feel that in the space. They have good signage, good organization of tools. It sounds simple but their spaces are designed for people. I’m not used to this kind of organization [in Armenia]. Even in the airport, everything was self-driven (self-check-in etc.). When you’re in that environment you feel that your efficiency grows. And you begin to think that way as well.

I heard this sentence once in Armenia, but I only experienced it in Finland: “The universal goal of education is to make people self-reliant”. That’s really the future. Empowering people to be self-driven, self-motivated, and self-reliant. It’s a new form of literacy and that is Finland.

Design Factory (DF) or Aalto Design Factory (ADF) is one of the three factories of Aalto University in Otaniemi, located in Betonimiehenkuja 5, in Espoo, Finland. The purpose of the Design Factory is to be a constantly developing environment for learning, teaching, research and industry co-operation related to product development and design. The director of Design Factory is professor Kalevi Ekman. The current company partners of DF are Nokia (supporting partner), Kone (project sponsor), Aito, Bravo Media, Powerkiss, Seos Design, Uploud Audio, and Veturi Growth Partners. Also, some non-profit organizations have their premises on Design Factory. There are also research projects going on at DF.

Kalevi “Eetu” Ekman: Professor of Machine Design at Aalto University School of Engineering and the Professor responsible for PdP. He is also the Director of Aalto University Design Factory, an experimental co-creation platform for education, research and application of product design. His research and education activities relate to integrated product development process, conceptual design phase, prototyping, and especially interdisciplinary co-creation between engineers, designers, and business professionals.